- Biblioteca CEPAL

- Biblioguias

- biblioguias_en

- 75 years of ECLAC and ECLAC thinking

- The 1980s: the debt crisis

75 years of ECLAC and ECLAC thinking

The 1980s: the debt crisis

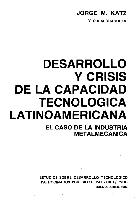

Press conference by the Executive Secretary of ECLAC, Enrique V. Iglesias

End-of-year press conference by Mr. Enrique V. Iglesias, Executive Secretary of ECLAC.

ECLAC, Santiago, December 1980

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

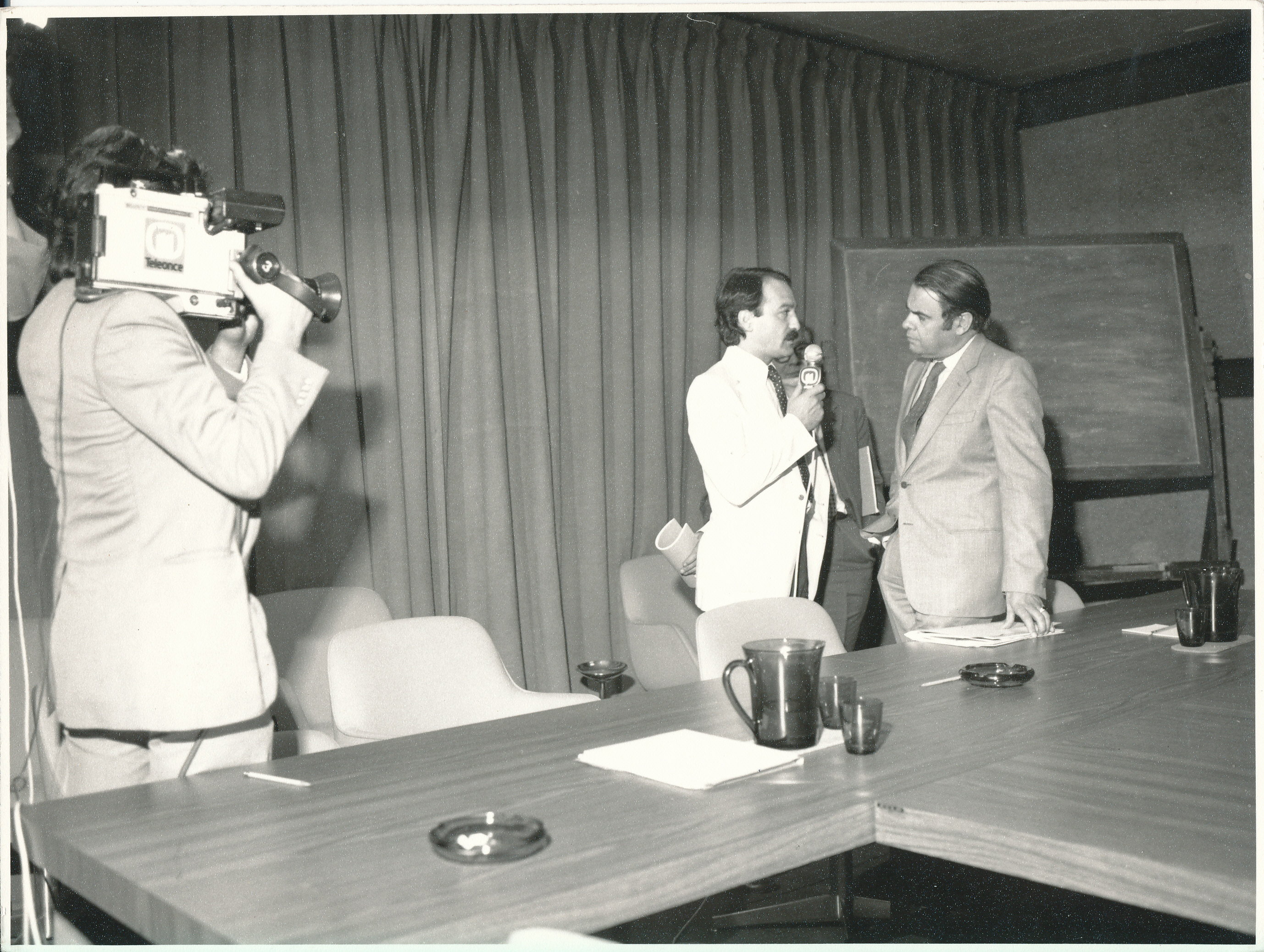

Regional Seminar on the Law of the Sea, ECLAC

Enrique V. Iglesias, Executive Secretary of ECLAC (second from right to left) in a presentation during the Regional Seminar on the Rights of the Sea.

ECLAC, Santiago, September 13-15, 1982

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

Signature of the technical cooperation agreement with the Government of France

Enrique V. Iglesias, Executive Secretary of ECLAC (right) together with Robert Hourcaillo, Ambassador Plenipotentiary of France at the signing of a technical cooperation agreement with the ECLAC system.

Santiago, August 23, 1984

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

Sixth Regional Conference of Ministers of Education and Ministers in Charge of Economic Planning of the Member States of Latin America and the Caribbean

Press conference by the Executive Secretary of ECLAC, Norberto González, during the Sixth Regional Conference of Ministers of Education and Ministers in Charge of Economic Planning of the Member States of Latin America and the Caribbean, organized by UNESCO.

United Nations Information Center - Bogota, Colombia, March 30, 1987

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

Funeral of Raúl Prebisch in the ECLAC Building

Relatives, friends, colleagues and high-level officials at the funeral of Raúl Prebisch, former ECLAC Executive Secretary at the ECLAC Building.

ECLAC, Santiago, April 30, 1986.

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

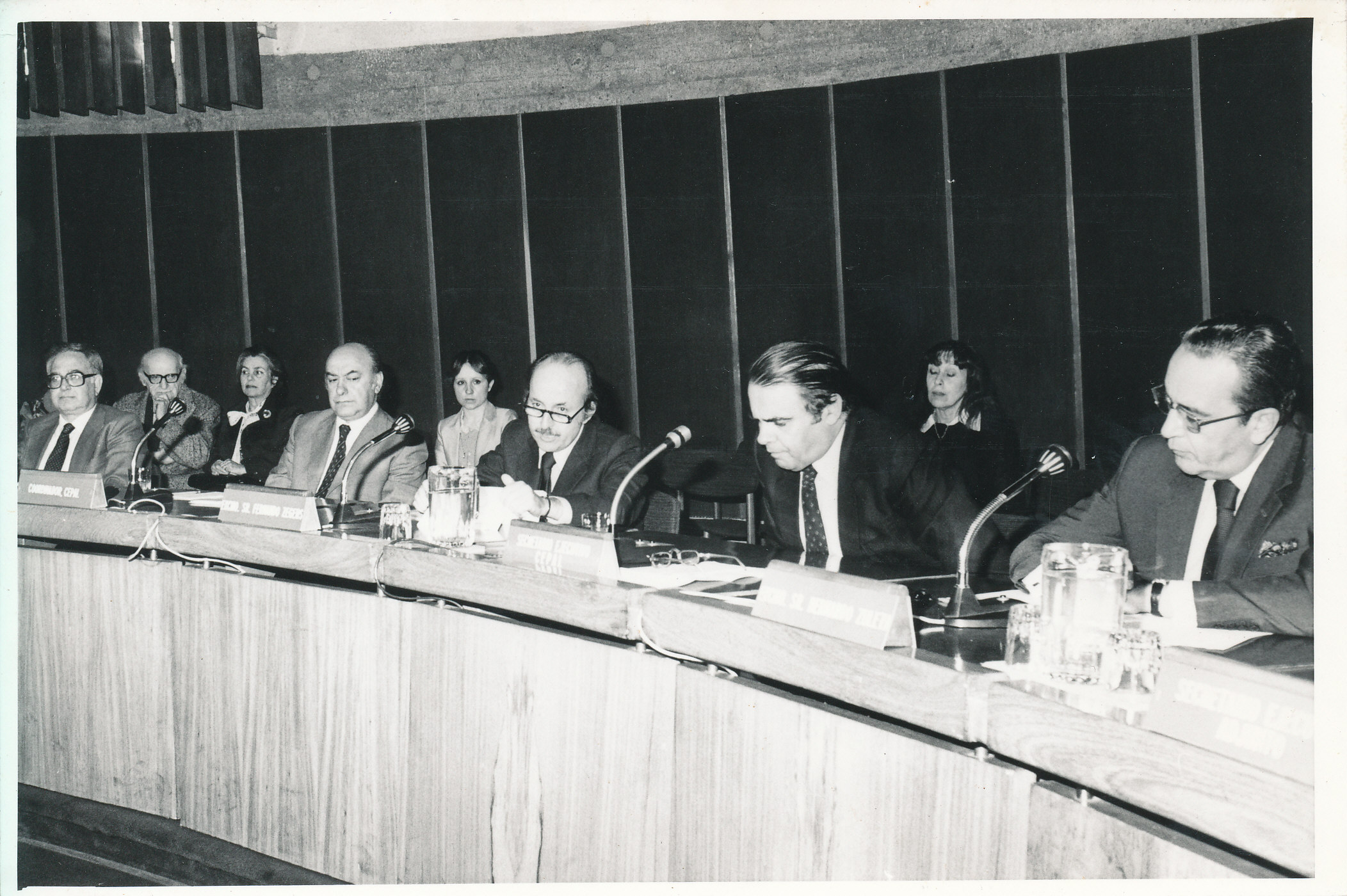

Exhibition of ECLAC publications during UN Week

Norberto González, ECLAC Executive Secretary with Gert Rosenthal, Deputy Executive Secretary for Economic and Social Development and Robert T. Brown, Deputy Executive Secretary for Cooperation and Support Services in front of UN publications during the celebration of the UN Week 20-24 October 1986.

Santiago, October 1986

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

Visit of Pope Juan Pablo II to ECLAC

Gert Rosenthal, Deputy Executive Secretary for Economic and Social Development greets Pope Juan Pablo II upon his arrival at ECLAC.

Santiago, April 3, 1987

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

See also: Towards an economy of solidarity. Message from His Holiness John Paul II on the occasion of his visit to ECLAC Headquarters, Santiago de Chile, April 3, 1987.

Inauguration of the first stone for the construction of the CELADE building

Gert Rosenthal, Executive Secretary of ECLAC lays the first shovelful of soil for the construction of the new building of the Latin American and Caribbean Demographic Center (CELADE).

Santiago, March 30, 1988

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

Signing of cooperation agreements between the Government of Italy and ECLAC

Meeting of representatives of the Government of Italy and ECLAC authorities for the signing of two cooperation projects. From left to right: Robert T. Brown, ECLAC Deputy Executive Secretary; Armando Sanguini, Chargé d'Affaires of Italy; José Roberto Jovel, Director of ECLAC's Operations Division and Gert Rosenthal, ECLAC Executive Secretary. The first "Support to the governments of the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean for economic recovery and development" aims to support the governments of the region in the formulation and implementation of plans for economic recovery and the development. The second will be dedicated to the expansion of meteorological systems and the design of a methodology for the evaluation of damage caused by natural disasters of all kinds, in collaboration with the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

Santiago, February 1988

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

ECLAC Executive Secretary, Gert Rosenthal meets with the UN Secretary-General, Javier Pérez de Cuellar

The Secretary-General of the UN, Javier Pérez de Cuellar (left) meets with Gert Rosenthal after assuming the new position as Executive Secretary of ECLAC.

United Nations, New York, January 19, 1988

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

The profound economic and social crisis affecting most of the countries of the region during the 1908s led then Executive Secretary, Norberto González (1985–1987), to describe the period as “the lost decade”.

The focus of this decade was on renegotiating external debt and making macroeconomic adjustments to return to economic growth, and implementing policies to mitigate the social costs of the debt crisis.

Towards the end of the 1980s, the region was beginning to recover from the “lost decade”, while many of the countries had returned to or were moving towards democracy. ECLAC thinking was given a fresh impetus, with the conviction that economic growth was inseparable from social equity. Fernando Fajnzylber (1990) was the first to offer theoretical and empirical arguments for this hypothesis. (Industrialización en América Latina: de la "caja negra" al "casillero vacío". Cuadernos de la CEPAL, No. 60, 1990)

Selected texts 1980-1989

“In the eighties, known as "the lost decade", due to the drop in regional per capita income caused by the debt crisis, ECLAC's work was conditioned by the context of recessive adjustments practiced in most of the countries region. This led to a reduction in the relative importance of the two main topics until then —productive development and equality— and to reorient priorities towards a field in which the institution had not intervened much in previous decades, namely, the analysis of macroeconomic stability and especially of the debt-inflation-adjustment trilogy.” [Free translation] (Reflexiones sobre el desarrollo en América Latina y el Caribe: conferencias magistrales 2015. CEPAL, 2016., p. 58)

Featured Documents

-

Capitalismo Periférico: crisis y transformación by

Publication Date: 1981México: Fondo de Cultura Económica -

Dinámica del capitalismo periférico y su transformación

by

Call Number: E/CEPAL/R.215Publication Date: 7 de febrero de 1980

Dinámica del capitalismo periférico y su transformación

by

Call Number: E/CEPAL/R.215Publication Date: 7 de febrero de 1980 -

La dimensión ambiental en los estilos de desarrollo de América Latina

by

Call Number: E/CEPAL/G.1143Publication Date: julio de 1981Libros de la CEPAL

La dimensión ambiental en los estilos de desarrollo de América Latina

by

Call Number: E/CEPAL/G.1143Publication Date: julio de 1981Libros de la CEPAL -

La Industrialización trunca de América Latina

by

Publication Date: 1983México, DF: Editorial Nueva Imagen

La Industrialización trunca de América Latina

by

Publication Date: 1983México, DF: Editorial Nueva Imagen -

Demografía histórica en América Latina: fuentes y métodos

by

Publication Date: abril de 1983Serie E - CELADE (San José), No.1002

Demografía histórica en América Latina: fuentes y métodos

by

Publication Date: abril de 1983Serie E - CELADE (San José), No.1002 -

Bases for a Latin American response to the international economic crisis

by

Call Number: E/CEPAL/G.1246Publication Date: 16 May 1983

Bases for a Latin American response to the international economic crisis

by

Call Number: E/CEPAL/G.1246Publication Date: 16 May 1983 -

Problemas económicos del Tercer Mundo

by

Publication Date: noviembre de 1983Proyecto(s): Programa de Estudios Conjuntos sobre las Relaciones Internacionales de América Latina Datos Buenos Aires: Editorial de Belgrano

Problemas económicos del Tercer Mundo

by

Publication Date: noviembre de 1983Proyecto(s): Programa de Estudios Conjuntos sobre las Relaciones Internacionales de América Latina Datos Buenos Aires: Editorial de Belgrano

-

Políticas de ajuste y renegociación de la deuda externa en América Latina

Call Number: LC/G.1332ISBN: 9789509432147Publication Date: diciembre de 1984Cuadernos de la CEPAL, No. 48

Políticas de ajuste y renegociación de la deuda externa en América Latina

Call Number: LC/G.1332ISBN: 9789509432147Publication Date: diciembre de 1984Cuadernos de la CEPAL, No. 48 -

-

The decade for women in Latin America and the Caribbean: background and prospects

Publication Date: 1986Libros de la CEPAL, No. 11

The decade for women in Latin America and the Caribbean: background and prospects

Publication Date: 1986Libros de la CEPAL, No. 11 -

Latin America: international monetary system and external financing

by

Publication Date: 1986Libros de la CEPAL, No. 12

Latin America: international monetary system and external financing

by

Publication Date: 1986Libros de la CEPAL, No. 12 -

Latin American and Caribbean development: obstacles, requirements and options

Publication Date: junio de 1987Cuadernos de la CEPA, No.55

Latin American and Caribbean development: obstacles, requirements and options

Publication Date: junio de 1987Cuadernos de la CEPA, No.55 -