- Biblioteca CEPAL

- Biblioguias

- biblioguias_en

- 75 years of ECLAC and ECLAC thinking

- The 2000s: globalization, development and citizenship

75 years of ECLAC and ECLAC thinking

The 2000s: globalization, development and citizenship

Seminar on Globalization ECLAC-World Bank

From left to right: Daniel Blanchard, Secretary of the Commission, ECLAC; Guillermo Perry, Chief Economist for Latin America and the Caribbean, World Bank; José Antonio Ocampo, Executive Secretary of ECLAC; Ricardo Lagos, President of Chile; David de Ferranti, Vice President for Latin America and the Caribbean, World Bank; Reynaldo F. Bajraj, Deputy Executive Secretary, ECLAC.

Santiago, March 6-8, 2002

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

Second Meeting of Former Ibero-American Presidents "The Social Agenda in Globalization"

José Antonio Ocampo, Executive Secretary of ECLAC together with Ricardo Lagos, President of Chile upon leaving the Second Meeting of Former Ibero-American Presidents "The Social Agenda in Globalization", organized by the José Ortega y Gasset Foundation, the Andean Corporation of Development and ECLAC. Event held in the Raúl Prebisch Hall of ECLAC.

Santiago, April 22, 2002

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

Visit of the President-elect of Brazil to ECLAC

The Executive Secretary of ECLAC, José Antonio Ocampo addresses the press during the arrival of the president-elect of Brazil, Luis Inácio "Lula" da Silva at ECLAC.

Santiago, December 3, 2002

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

Kofi Annan, UN Secretary-General visits ECLAC in Santiago, Chile

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan visits the Chilean capital for the first leg of his four-country South American tour. Mr. Annan (centre) at the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) headquarters in Santiago.

Santiago, November 6, 2003

Credit: UN Photo/Stephenie Hollyman

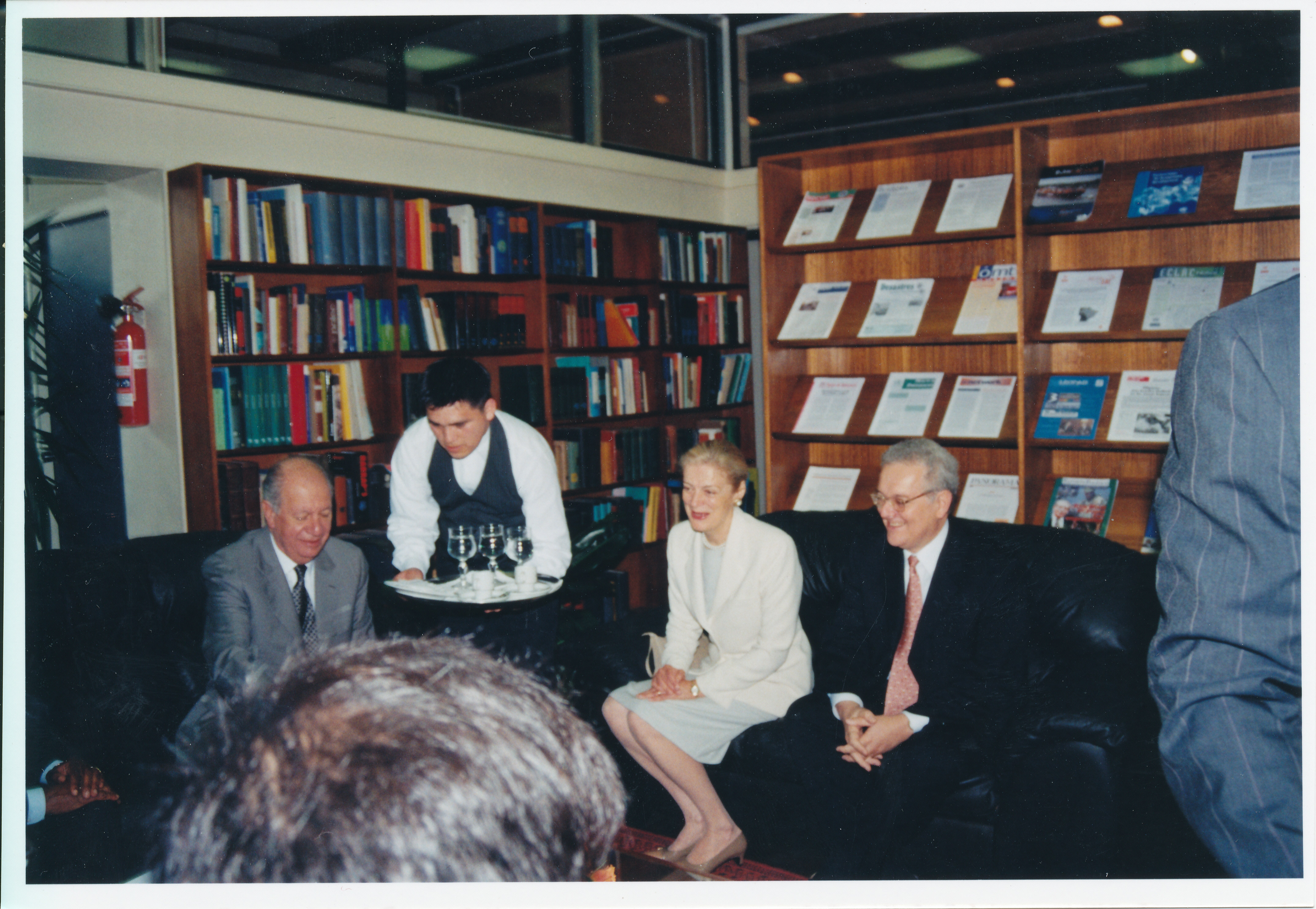

Visit of the UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, to ECLAC, 2003

Seated from left to right: Ricardo Lagos, President of Chile, Nane Annan, Kofi Annan's wife and José Antonio Ocampo, ECLAC Executive Secretary, during a welcome reception at the ECLAC Library.

Round table "The Global Context and the Renewal of the United Nations" (The global context and the renewal of the United Nations) held in the Raúl Prebisch Room at ECLAC headquarters.

Santiago, November 6, 2003

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

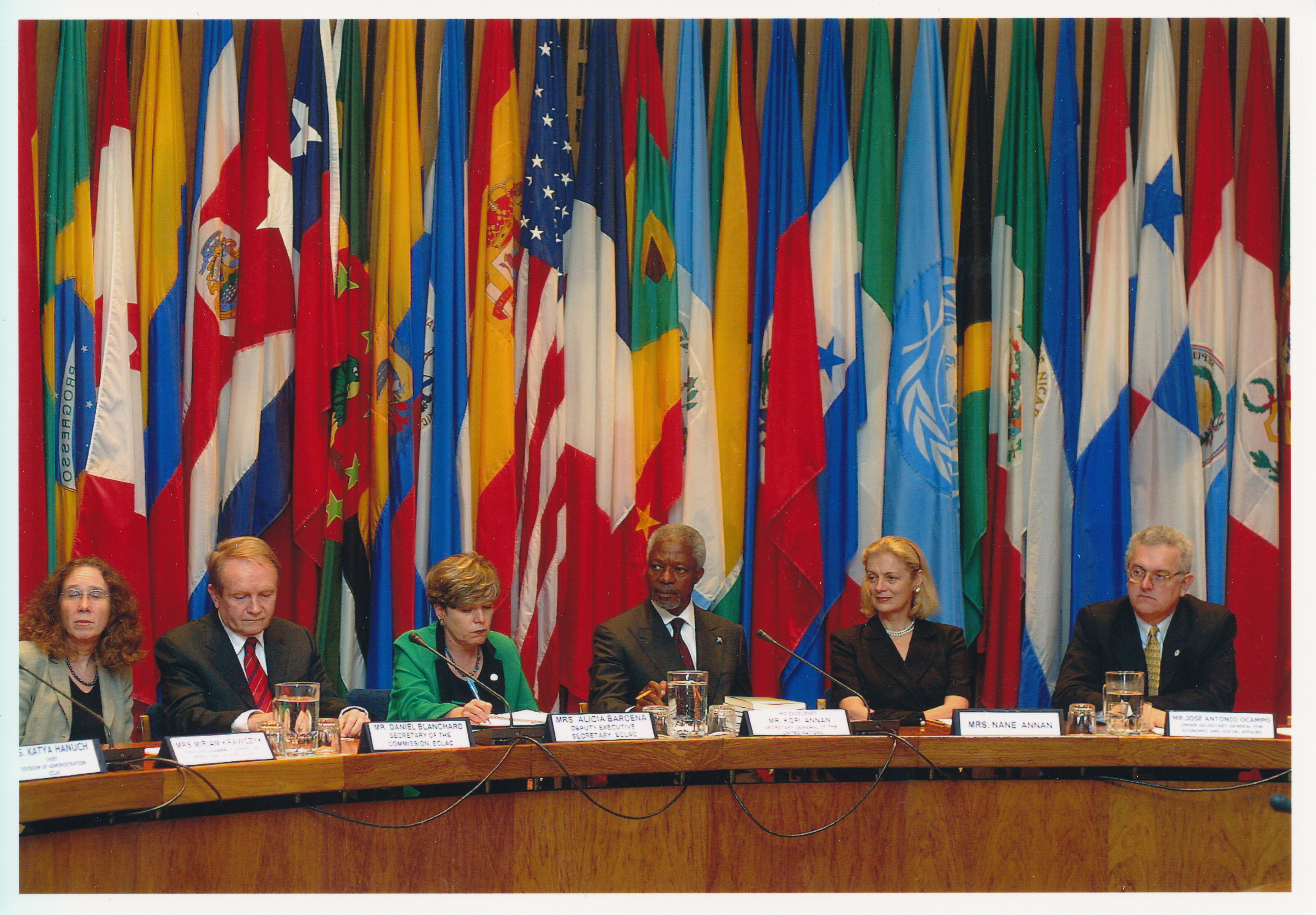

Visit of the UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, to ECLAC, 2003

The UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, meets with the Directors of ECLAC. The meeting was held in the Celso Furtado Room at the ECLAC headquarters. Seated from left to right: Miriam Krawczyk, Director of the Program Planning and Operations Division, ECLAC; Daniel Blanchard, Secretary of the Commission, ECLAC; Alicia Bárcena Deputy Executive Secretary, ECLAC; Kofi Annan, UN Secretary General; Nane Annan, wife of Kofi Annan, UN Secretary-General and José Antonio Ocampo, Executive Secretary of ECLAC.

Santiago, November 6, 2003

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

Visit of the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, to ECLAC, 2003

The UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, and Nane Annan (center) with ECLAC staff.

Santiago, November 6, 2003

Credit: ECLAC, United Nations

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon meets with ECLAC staff

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon shakes hands with the staff of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

Santiago, November 8, 2007

Credit: UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe

UN Secretary-General swears in new Executive Secretary of ECLAC

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon swears in Alicia Bárcena Ibarra as the new Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

United Nations, New York, May 28, 2008

Credit: UN Photo/Paulo Filgueiras

The fast-moving process of globalization at the start of the twenty-first century opened up opportunities for the region, but also gave rise to new development challenges. Together, the extraordinary growth in world trade and rapid technological change led to an increase in inequalities within and between nations, while the pattern of growth led to accelerated environmental deterioration around the globe.

In September 2000, after a decade of major United Nations conferences and summits, world leaders gathered at United Nations Headquarters in New York to adopt the Millennium Declaration, committing their countries to achieving a set of eight predominantly social goals by 2015, known as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

The MDGs included efforts in a variety of areas, from halving extreme poverty rates to halting the spread of HIV/AIDS or providing universal primary education, forming a framework and galvanizing unprecedented action to meet the needs of the world’s poorest populations. In line with the MDGs, since the beginning of the twenty-first century ECLAC has emphasized the social dimension in its work, while increasingly integrating the dimension into its economic and institutional analyses and proposals.

The Millennium Declaration stated that the central challenge at that time was to ensure that globalization became a positive force for all the world’s people, while also acknowledging that its benefits were very unevenly shared and its costs were unevenly distributed: “only through broad and sustained efforts to create a shared future, based upon our common humanity in all its diversity, can globalization be made fully inclusive and equitable.”

In line with this vision, in its sixth decade ECLAC called for balancing of the asymmetries of globalization to achieve development based on productive transformation, distributive equity and social protection and cohesion.

Selected text 2000-2009

“In its sixth decade of existence, ECLAC continued the work of the previous 50 years, focusing especially on perfecting and maturing the neo-structuralist approaches of the 1990s. To do this, it was able to evaluate the results of the liberalizing reforms in light of the economic and social performance of the region and after almost a decade of intense discussions on the matter. Likewise, the institution's thinking evolved amid of a significant loosening of the ideological debate, caused by the weakening of the hegemonic neoliberal thinking in the region due to the successive cyclical disturbances of the late 1990s and early 1990s.” [Free translation] (Reflexiones sobre el desarrollo en América Latina y el Caribe: conferencias magistrales 2015. CEPAL, 2016., p. 61)

Position Papers of the Sessions of the Commission

Productive development in open economies

LC/G.2234(SES.30/3)

Publication date: June 2004

Shaping the future of social protection: access, financing and solidarity

LC/G.2294(SES.31/3)

Publication date: February 2006

Structural change and productivity growth, 20 years later: old problems, new opportunities

LC/G.2367(SES.32/3)

Publication date: May 2008

Featured Documents

-

A decade of light and shadow: Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1990s

by

Publication Date: 2002

A decade of light and shadow: Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1990s

by

Publication Date: 2002 -

CEPAL Review No. 75

Call Number: LC/G.2150-PPublication Date: December 2001This issue of CEPAL Review includes a tribute to Raúl Prebisch on the centenary of his birth, with a set of articles by distinguished personalities from the social sciences linked to thought on Latin America.

CEPAL Review No. 75

Call Number: LC/G.2150-PPublication Date: December 2001This issue of CEPAL Review includes a tribute to Raúl Prebisch on the centenary of his birth, with a set of articles by distinguished personalities from the social sciences linked to thought on Latin America. -

A decade of social development in Latin America, 1990-1999

Call Number: LC/G.2212-PPublication Date: March 2004Libros de la CEPAL, No.77

A decade of social development in Latin America, 1990-1999

Call Number: LC/G.2212-PPublication Date: March 2004Libros de la CEPAL, No.77 -

Reformas para América Latina después del fundamentalismo neoliberal

by

Publication Date: 2005

Reformas para América Latina después del fundamentalismo neoliberal

by

Publication Date: 2005

-

-

Fernando Fajnzylber: una visión renovadora del desarrollo en América Latina

by

Call Number: LC/G.2322-PPublication Date: noviembre de 2006Libros de la CEPAL, No. 52

Fernando Fajnzylber: una visión renovadora del desarrollo en América Latina

by

Call Number: LC/G.2322-PPublication Date: noviembre de 2006Libros de la CEPAL, No. 52 -

Sixty years of ECLAC: structuralism and neo-structuralism

by

Publication Date: April 2009In: CEPAL Review, No.97, pp. 173-194.

Sixty years of ECLAC: structuralism and neo-structuralism

by

Publication Date: April 2009In: CEPAL Review, No.97, pp. 173-194. -

Sesenta años de la CEPAL: textos seleccionados del decenio 1998-2008

by

Publication Date: 2010

Sesenta años de la CEPAL: textos seleccionados del decenio 1998-2008

by

Publication Date: 2010